Film reviews: My Name is Alfred Hitchcock | The Deepest Breath

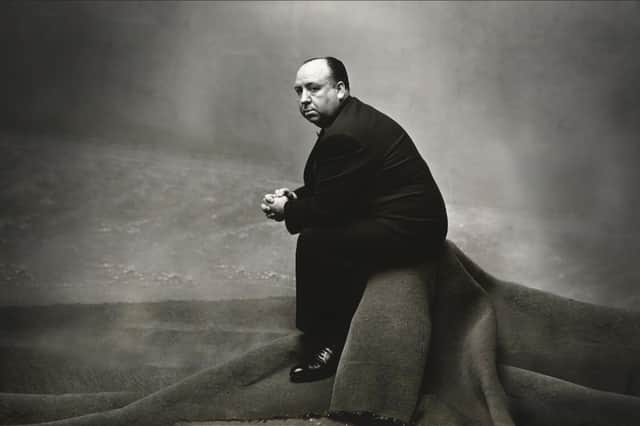

My Name is Alfred Hitchcock (15) ****

The Deepest Breath (12A) ***

Mark Cousins returns with another deep-dive into cinema history, this time with a playful exploration of the master of suspense Alfred Hitchcock. Unlike many of Cousins’s other cine-essays – his Story of Film opus, say, or The Eyes of Orson Wells – the Edinburgh-based filmmaker takes more of a back seat in My Name is Alfred Hitchcock, limiting his usually omnipresent voice to a couple of intrusions into his titular subject’s own analysis of his extensive body of work. Well, sort of… The opening credits may claim this is “written and voiced by Alfred Hitchcock”, kidding us on, perhaps, that it’s going to be another biographical documentary made up of some recently unearthed cache of never-before-heard audio interviews. But the familiar, deliberative, gently sardonic London-accented voice we’re confronted with belongs instead to impressionist Alistair McGowan, whom Cousins has impishly enlisted so he can analyse his work as if the man himself is communing with us from beyond the grave. The point is that Hitchcock’s voice is still very much alive in his films, so why not bring it back from the dead to discuss them?

The ruse works in part because Hitchcock was a cinematic trickster who fought against convention at every turn, and this film has been conceived in the same spirit. But it also works because Hitchcock was great at cutting through the analytical pomp that often greeted his work. Listen to him discuss his films during those famous interviews with Francois Truffaut in 1962 or the lengthy one Peter Bogdanovich did with him the following year and you’ll hear a charismatic artist talk with precision and humour about how cinema works and how he mastered its techniques to tell the stories he wanted to tell. And Cousins is good at filtering his own insights into Hitchcock’s work through this act of mimicry. Using a multitude of clips that run the gamut from Hitchock's early silent films to the classics imprinted on every film lover’s brain and continuing on to his lesser regarded later films, he splits his movie into six chapters, each dealing with a different theme. The first section, “escape”, is the longest, swiftly followed by meditations on “desire”, “loneliness", “time”, “fulfilment” and “height”. In each Cousins’ instinctive ability to cut together clips of seemingly disparate films to illuminate some technique or trick to engage an audience has the collective effect of opening the movies up like the door Hitchcock sometimes deployed at the start of his own films to subliminally invite us into the worlds he was creating. True, some of it might seem obvious to seasoned cinephiles. But there’s also something to be said for taking the time to look, really look, at what Hitchcock was doing on screen and Cousins – via McGowan – is a fine guide.

Advertisement

Hide AdA few years ago, rock-climbing documentary Free Solo demonstrated the extent to which a non-fiction film could compete with a Tom Cruise movie when it came to capturing insanely dangerous, heart-in-mouth feats of human endurance on screen. Now comes the underwater version. The Deepest Breath delves into the rarefied world of free diving, an even more extreme sport which requires participants to hold their breath for up to three minutes and dive to depths of 100 metres or more just to prove they can. It’s extraordinarily dangerous and can’t be done without a team of safety divers willingly risking their own lives to pull participants up if their lungs give out and their brains start shutting down. Indeed, the film gives us a sense of just how dangerous it is early on, with footage of a diver blacking out on the return ascent before being instantly resuscitated with mouth-to-mouth the moment they reach the surface. It’s a horrific sight: their eyes scarily wide, their face scarlet, they look like the adult equivalent of panicked newborn taking their first breath.

Given that this is a sport that not only puts participants in close proximity to death with every competitive dive, but risks scarring their lungs so severely it’s not unheard of for former free divers to be on oxygen for the rest of their lives after they hit their 40s, it’s hard to fathom what people get out of the sport beyond the masochistic desire to push themselves to the limit. The film’s Irish director Laura McCann never quite gets to the bottom of its appeal either, although to be fair, The Deepest Breath isn’t really about why people do it. Her interest lies instead in Italian world-record holder Alessia Zecchini and her Irish boyfriend Stephen Keenan, who found each through free diving and paid a tragic price for their pursuit of it. That’s not really a spoiler; the film is so blatant about presenting their dual stories through home movies and solemn talking-head interviews with friends and family who only ever refer to them in the past tense that you know something has gone terribly wrong on a dive. But given where the film goes, there’s something a little disingenuous about McCann’s decision to omit certain voices so she can build suspense and deliver a cheap rug-pulling finale. As a portrait of a weird subculture it’s frequently fascinating, but as a film about a diving couple, its insights into their tragically curtailed relationship are frustratingly shallow.

My Name is Alfred Hitchcock is on selected release; The Deepest Breath is available to stream on Netflix